War Dogs of World War 2

Sicily, July 1943. American soldiers are pinned down by heavy fire from an Italian pillbox. Time to bring forward their top weapon. What will it be? A bazooka? A flamethrower? How about a Sherman tank? No. This weapon has four legs, sharp teeth, and answers to the name Chips.

Humans have worked with domesticated dogs for somewhere like 20,000 years. Hunting, defence, companionship- wherever we go, they go too. And war is no exception. The ancient Romans and Greeks used dogs as messengers and on sentry duty. The Roman general Scipio Africanus apparently sent mighty Molossus dogs into battle wearing spiked collars.

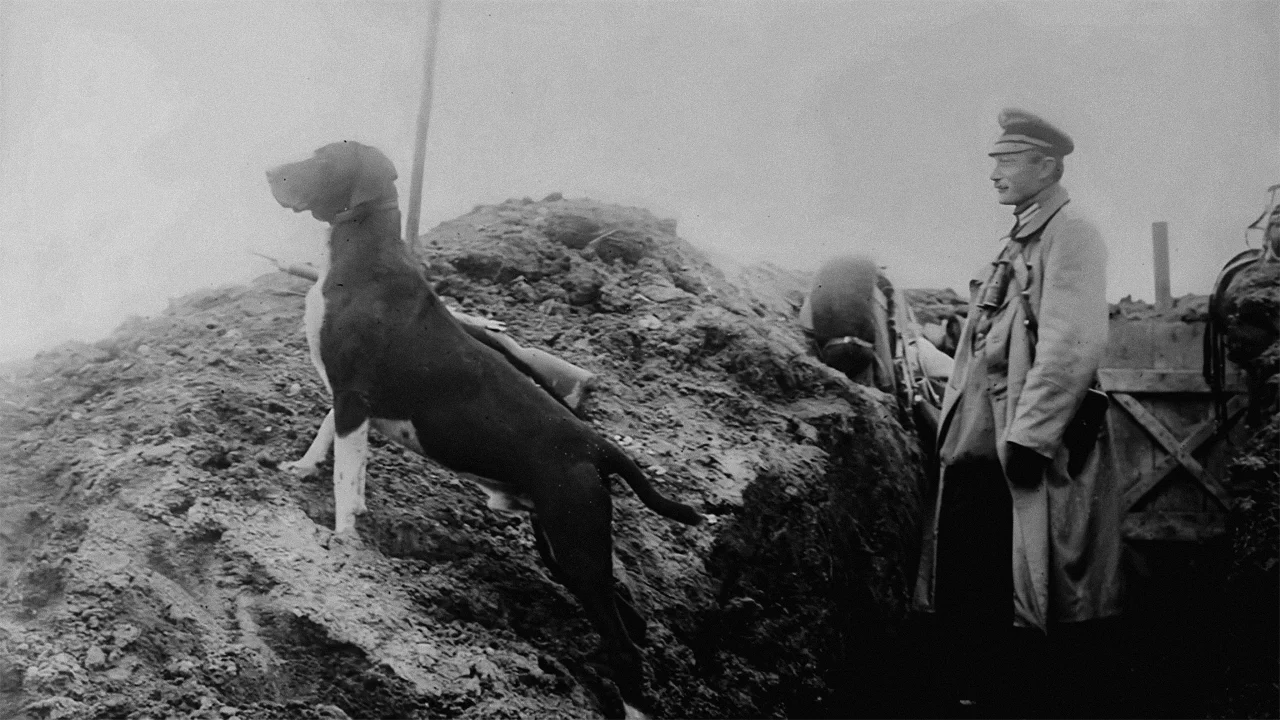

During the Great War, dogs on all sides held a variety of roles. Sentry dogs were trained to growl or raise their hackles when they caught the scent of an intruder.

Rescue dogs sought out wounded soldiers and guided stretcher-bearers.

Packs of dogs were trained to pull crew-served weapons like machine guns.

Dogs carried messages and ammunition, and even laid telephone cables. All in all, some 20,000 dogs served with British forces alone during that war.

So, it’s no surprise that dogs are called up again when war breaks out in 1939.

The German Army goes to war with a well-established dog-training programme. No prizes for guessing the breed of choice. It’s the Altdeutsche Schäferhunde or the German Shepherd. Although interestingly enough, it’s known as the Alsatian in Britain and was in parts of the states – having been renamed at the height of anti-German feeling in the Great War.

At eight weeks old, they begin an eight-week training programme. The dogs are tested for their ability to follow their owner by day and night, to climb stairs, cross ditches, and streams, and to cope with the sound of gunfire.

The German Shepherd is Heinrich Himmler’s personal favorite breed too. Perhaps this is because the dogs have been incorporated into Nazi ideology. As far back as 1923, German nationalists were writing of the Aryan mysticism which guided the bond between the German man and German Shepherd. Or perhaps it’s because his boss, Adolf Hitler, owns two of them.

Each of Himmler’s concentration and death camps have a dedicated detachment of SS dog handlers. They use German Shepherds and Wolfhounds. The animals are kept in comfortable accommodation and their SS handlers pet them and play with them. But the dogs are trained to savagely attack any prisoners who try to escape, or sometimes, just because the guards feel like it, they will set the dogs loose. With a quick word or gesture, they will maim or kill men, women, and children.

They may be enemies on the battlefield, but the Germans and the Soviets agree on something. They’re both fans of the German Shepherd. The Soviets prize the dog for its physical strength and responsiveness to instruction. The Red Army has been training dogs since 1926 and somewhere in the region of 40,000 will have served by the end of the war.

There’s one particular group of dogs that you’ve probably heard of- the anti-tank dogs. These are dogs with anti-tank mines strapped to their backs in a pouch. They’re trained to expect food underneath tanks, so that in battle they’ll run under the panzers and detonate their explosives. It’s pretty depressing to think about. Not only do these dogs get blown to pieces but the last thing that goes through their mind is probably disappointment at not getting their dinner.

They are first deployed during Operation Barbarossa. This isn’t some sort of last-ditch plan, either. The programme began back in 1935 and trials were conducted in 1939 and 1940. There are some reports of dogs destroying tanks, a handful during Barbarossa, and a dozen at Stalingrad. It’s hard to know how many of these are accurate. But considering the Central Dog Training School had 3,000 anti-tank pouches ready in 1941, it doesn’t seem like a good return on so much investment.

The Germans certainly don’t see them as a serious threat. They simply shoot any dogs that approach their vehicles during battle. By the end of 1942, the programme is wound down. There’s mention of the dogs being deployed at Kursk in the summer of 1943, but by now the resources are being redirected to more useful avenues such as training dogs to detect mines rather than deploy them.

Neither the British nor the Americans are as well prepared as the Germans or Soviets when it comes to dogs. The British had allowed their training programme to lapse during the interwar years. However, in 1941 the War Office decides it need dogs to help guard supply depots, but because there hasn’t been any sort of organized breeding programme, they place ads in the newspapers encouraging pet owners to hand over their dogs.

Unfortunately, there’s something of a shortage. This is because of The British Pet Massacre of 1939. That was back that summer when the government was worried that pet owners would share their rations and end up going hungry. To try and prevent this from happening, a pamphlet was published which advised sending pets away to the countryside or placing them with a neighbour better equipped to look after them but the pamphlet concluded, “If you cannot place them in the care of neighbours, it really is kindest to have them destroyed.” It also advertised a bolt pistol marketed as “the standard instrument for the humane destruction of domestic animals”. This advice was also published in newspapers across the country, so when war broke out in September panicked animal owners flocked to clinics requesting their pets be put down.

There was another wave of euthanasia when the Blitz began in September 1940. Altogether some 400,000 dogs were killed along with hundreds of thousands of cats, birds, and other animals. Many pet owners soon came to regret their actions and blamed the government for whipping up panic. So, you’d think they might not receive the War Office’s 1941 appeal very well, but no, the public are highly enthusiastic. One widow’s reply reads, “My husband has gone, my sons have gone… take my dog to help bring this cruel war to an early end.” Within two weeks, 7,000 people have offered their dogs to the programme.

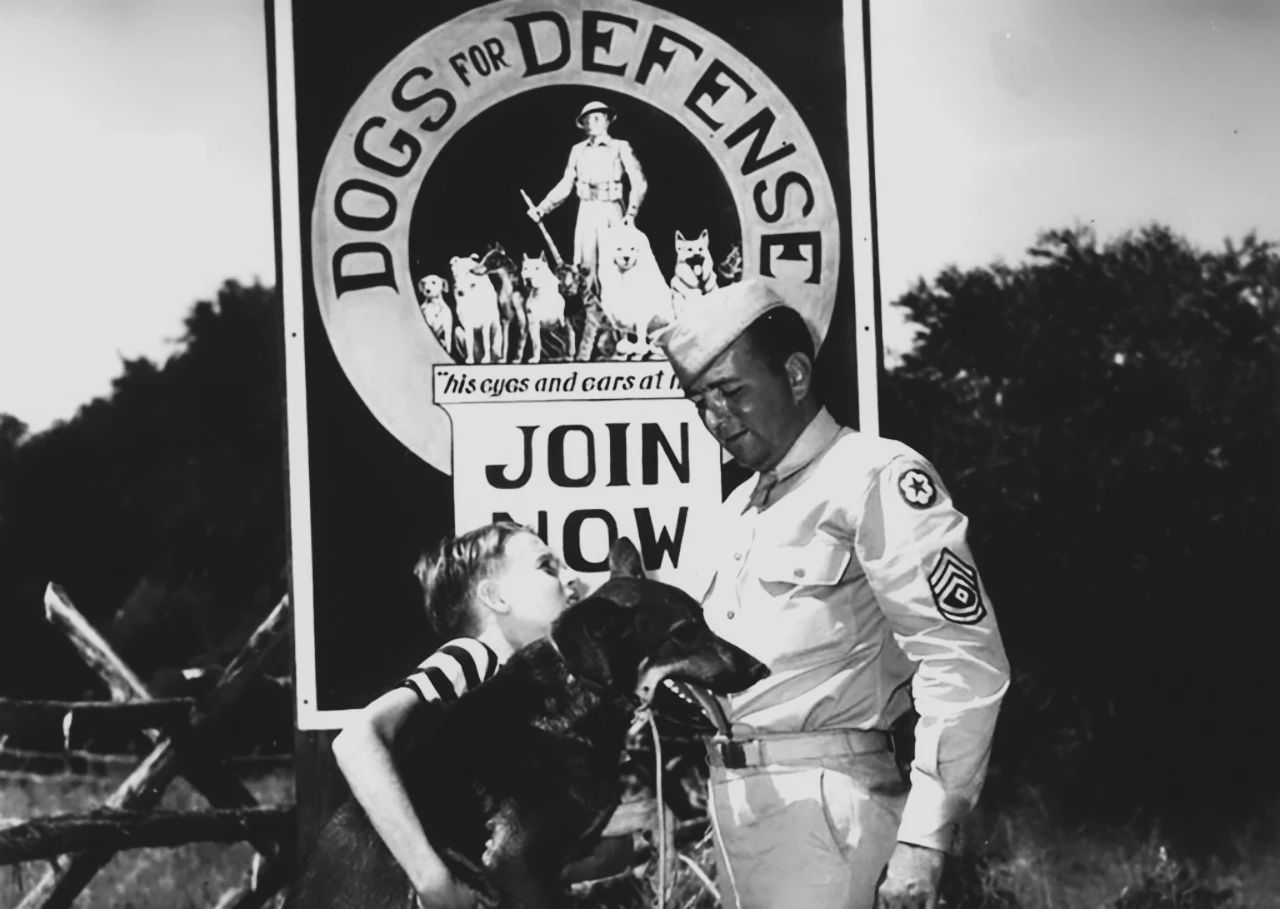

The story in America is similar. Minus the pet massacre. When the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor in 1941, the US Army possesses little more than a few sled dogs trained for working in arctic conditions. There’s neither the infrastructure nor the manpower – sorry, dogpower – necessary, so a group of civilians establish Dogs for Defense, DFD, which encourages dog owners to donate their pets for military use.

The founder of the organisation is Arlene Erlanger. She tells the New York Sun that “The dog must play its part in this thing”. By March 1942, the Army has come round to the idea. DFD unleashes a publicity blitz. Posters, radio shows, and even children’s books are pumped out to convince dog owners to give up their pets. There’s a children’s radio story about a boy named Davey. Too young to fight, Davey tells his dog Rusty “If I can’t do anything, you can go and fight in my place, can’t you, fella?”

Dog owners can donate their pets at any of the DFD regional offices. Here, they are given medical exams to determine their suitability for service. Initially, 32 breeds are accepted for training. But, by 1944 the Army will have narrowed this down to seven: German Shepherds, Doberman Pinschers, Belgian Sheep Dogs, Siberian huskies, farm collies, Eskimo dogs, and Malamutes.

By the end of the war, about 18,000 dogs will have signed on at the DFD offices. After that, it’s off to boot camp. These training centers are run by the Army’s newly established K-9 Corps. The dogs begin with obedience. They must learn to follow verbal commands and hand signals. Then it’s mobility: the dogs jump, crawl, swim, and climb their way through assault courses. They learn to ride in jeeps, war gas masks, and are desensitized to the sound of gunfire.

Just like human recruits, the dogs then go on to specialist training. Scout dogs are trained to work off the leash. Walking 30 to 40 yards ahead, they learn to alert their handlers to enemy presence. Each dog has two collars. One for work, and one for rest. That way, the dogs know when things are serious. Of those 18,000 dogs, some 10,000 pass training and are accepted for service.

Some of the war dogs display real heroism. American newspapers regularly report the latest heroics of the DFD dogs. Perhaps the most famous is a German Shepherd and Husky mix named Chips. He’s the dog mentioned at the beginning.

Chips serves in North Africa for Operation Torch. Then, during Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in the summer of 1943, he apparently singled-pawedely takes down an Italian pillbox. His story will be immortalized in a book by Mabel Harmer published in 1945.

Here’s what she will say about Chips and the attack on the pillbox. And bear in mind this is probably just a teeny bit exaggerated for effect: “The soldiers threw themselves upon the sand in order to escape the hail of bullets, but not Chips. With a total disregard of anything the enemy had, Chips charged the hut and came out with one Italian by the throat and three others holding their hands high above their heads…”

Chips will end up being the most decorated dog in this war. Yes, dogs can win medals too. By the end of this year, Chips will have been awarded a Purple Heart, a Silver Star, and the Distinguished Service Cross.

This will upset some of the human recipients of the Purple Heart and in 1944 dogs will be prohibited from receiving decorations.

In the UK, this problem is sidestepped by creating a separate award for animals. The first Dickin Medal will be awarded in December 1943. 18 dogs will end up receiving the award for their work during the war. These will include the Alsatians Jet and Irma who assisted with finding survivors in the Blitz; Antis, who accompanied his Czech master on flights with the RAF; and Judy, who kept morale up in a Japanese POW camp.

Dogs like these are the exception though. Most have far more mundane service lives. The vast majority of them, like 9,000 of those 10,000 American dogs for example, will spend their time performing sentry duty on military installations or patrolling coastlines.

The dogs make a real difference when it comes to the welfare of the men too. This is something that the armies aren’t entirely happy about. They don’t want soldiers getting attached to dogs who might very well die. The War Dogs Training school in Britain warns dog handlers in 1942, “Don’t make friends with or pet any of these dogs.” Unsurprisingly that proves to be a futile request.

The handlers and their dogs develop close bonds, and these quickly extend to the other men around them. That’s not surprising at all. Scientific studies long after the war will show the benefits to mental health of having a pet around. And it’s not just the dogs that are issued by the Army. In Cairo, British and Commonwealth soldiers return from the front with their trucks loaded up with rescued dogs and even desert foxes, and as they wander the streets of the city, they can’t help but purchase the puppies they see for sale.

The story of Chips, and the image of British soldiers and their new pets in Cairo, are heart-warming. But life isn’t all heroism and companionship. The animals in this war endure the same hardships as their human masters. They too get wounded and killed, catch diseases, and feel hunger, pain, and fear.

It’s not just dogs, either. The Germans have dragged tens of thousands of horses to the Eastern Front where winters are freezing cold, and summers are baking hot. In Sicily and Burma, the Allies load their mules up with water, ammunition, and weapons. And when the going gets tough, it’s the animals that end up losing out. When food or water is short, army quartermasters will always prioritize the men over the animals. When the food runs out… Well, let’s just say that during the worst months of the Siege of Leningrad, dogs weren’t pets, they were the difference between life and death for starving humans. And all these animals have been pressed into service without any real understanding of what is happening. Dogs like Chips are fighting bravely but he really has no choice in the matter, does he? And he doesn’t know why.