Yugoslav Resistance – Partisans and Chetniks

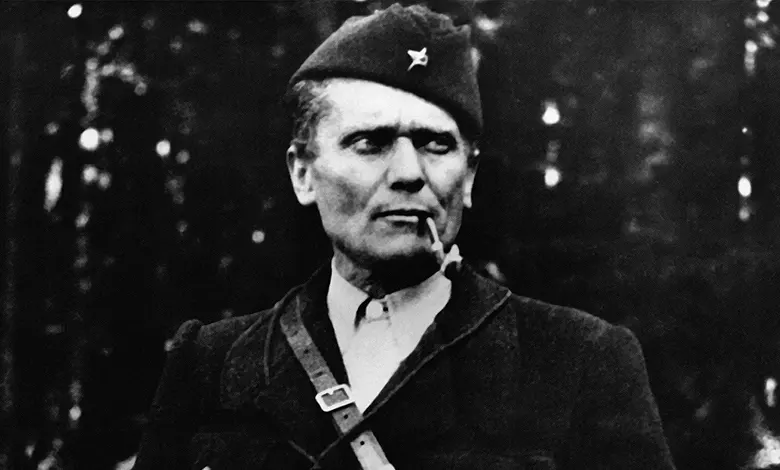

Soon after the German invasion of Yugoslavia, two major resistance movements emerge. They both fight for the restoration of Yugoslavia, but both have very different ideas on what that should look like. The multi-ethnic communist Partisans under command of Josip Broz Tito rival the Serbian Chetniks, leading to a political and military whirlwind in Yugoslavia in 1941.

After the invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the kingdom is carved up by the four antagonists: Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria. What was one country is now divided into nine different territories.

Large parts are occupied or annexed, such as Slovenia by Germany and Italy, parts of Serbia by Hungary and Macedonia by Bulgaria. The ‘Independent State of Croatia’ (NDH) becomes a German puppet.

Throughout former Yugoslavia, new regimes crackdown on different national and ethnic minorities.

In Croatia, the Ustase unleashes its draconian purges on the Serbs, who are killed, deported or forcibly converted en masse.

Large droves of people in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina are pushed into the ranks of the resistance movements by the harsh conditions under the new occupiers.

But it takes until Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union for the resistance to get into organised action.

Just after the invasion, Yugoslav communists laid low, not wanting to antagonise the Germans on behalf of the Soviet Union, honouring the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact.

Directly on June 22, as Germany invades the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, Croatian communists stage an uprising in Sisak.

On July 7, Josip Broz Tito starts a revolt of his own in Serbia.

He is one of the prominent leaders of the Partisan Movement, a name derived from the ‘National Liberation Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia’ – an armed wing of the Communist Party.

Tito was appointed General Secretary of the illegal Communist Party of Yugoslavia back in 1939. In that capacity, he was already running an underground partisan movement long before the Nazi’s invaded Yugoslavia.

Tito aims to unite all Yugoslav nations in the struggle, saying that ‘The words national liberation struggle would be nothing but words, and even deception . . . if they did not mean, together with the liberation of Yugoslavia, the liberation at the same time, too, of Croats, Slovenes, Serbs, Macedonians, Arnauts [Albanians], Moslems and the rest.’

His partisan movement is swiftly joined by people from all of these nationalities, though in 1941 the majority come from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia.

The uprising is quite successful. Germany, having its hands full with fighting the Soviets on the eastern front, has only left behind a small detachment of three divisions of second-rate troops to keep order.

The Partisans are hard to catch, operating from mountains and villages, and Tito’s uprising spreads rapidly through Western-Serbia.

In September 1941, he establishes his headquarters in Užice.

In every village that the very mobile Partisans forces take they set up an administration and logistical system. This method makes civilians in the region who are not joining the militia stakeholders in the resistance – which the Partisans double down on with grand propaganda campaigns. This grows into the so-called Užice republic – the first ‘liberated’ territory of World War Two in Western Serbia.

Other Yugoslavians join the Chetnik movement, created from leftovers of the Royal Yugoslav Army by Serbian Nationalists. Many of its soldiers are ex-military who have fled to the mountains shortly after the German victory. Their most prominent leader is Draža Mihailović, who enjoys support from the Serbian government in exile in London.

The Chetnik’s primary goals are to create a Serbian ethnic state in a Yugoslav Monarchy. To many Chetniks this carries with it a will to purge Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina of Croats, Muslims and Jews.

Nonetheless, they initially join the Partisans’ uprising, abiding by the credo ‘One Country, Two Masters’.

However, the Chetniks are scattered throughout the many Serbian villages, whereas the Partisan movement is centred around the Communist Party and its leaders.

The Chetniks main operation centers are their villages, while the Partisans, bound to ideology rather than geography, are more mobile and flexible.

The lack of Central organisation makes it hard to pin-point the Chetniks on the ideological scale.

Some openly advocate collaborating with the Germans and Italians to build the Serbian nation within the axis framework.

Others are fanatically anti-German, and advocate to join the Partisans, while others are fiercely anti-partisan.

Both the differences in ideological goals and operational organization makes a hard split between the Partisans and Chetniks seem unavoidable.

In any case, many Yugoslavs were driven to join the resistance movements as a reaction to Axis violence.

Like in October 1941, when German Führer Adolf Hitler orders the shooting of 100 Serbs for every German soldier killed, and 50 for every German wounded.

For every such new retaliatory action by the Germans, Italians, Bulgarians or Ustase Croats the Partisans movement grows. This becomes part of Tito’s deliberate strategy.

His forces ambush German strongpoint with sometimes reckless hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, triggering Axis reprisals, which only increases support for the resistance.

The recklessness lead to direct civilian deaths, compounded by the reprisals, and this concerns some of the Chetniks. Their war-goal is the survival of the Serbian Nation, not the defeat of the Nazi regime or the establishment of a multi-ethnic communist state. They don’t necessarily care about the clash of ideologies in the same way the Communists do.

The order to shoot 100 Serbs for every German results in the Kraljevo Massacre on October 20, where roughly 2,000 Serbs are killed.

Another one follows in Kragujevac where 2,324 are killed for a Partisan attack on Milanovac.

Retaliatory actions like that result in the deaths of 25,000 Serbs between October and December 1941 alone.

The Chetniks now become increasingly reluctant to provoke any anti-Serbian actions from the Germans. So, instead of active resistance, more and more Chetniks start to engage in passive resistance, or even passive collaboration.

A German representative in Serbia writes, 5 months into the occupation of Yugoslavia, that there had been no battles between German forces and Chetniks to date – although other accounts show Chetniks resisting alongside the Partisans.

The shift from resistance to collaboration is voiced in multiple groups within the Serbian nation.

On August 13, 1941, a large group of 545 Serbs, including bishops, archpriests, 81 professors, generals, former ministers, directors and journalists, publish an ‘Appeal to the Serbian Nation’ in major Belgrade papers, saying: ‘In these fateful hours, it is the duty of each Serb, each true patriot, to help the country preserve peace and order with all his might. […] a handful of alien mercenaries and saboteurs under the command of criminal Bolsheviks senselessly jeopardizes all efforts to settle our situation. […] The duty of each true Serbian patriot is to thwart the infernal intentions of the communist criminals with all his might. Therefore, we call upon the entire Serbian nation to assist our authorities in the struggle against these enemies of the Serbian nation and its future by acting decisively in every situation, using all available means.’

The Germans respond by installing a government in Serbia under leadership of one of the signatories, General Milan Nedić – Who is now in charge of building up pro-nazi forces in Serbia.

In late September, Chetnik leader Kosta Pećanac openly aligns himself with Nedić’s collaborationist government. By the autumn of 1941, Draža Mihailović too turns on the Partisans. Sharing a common enemy with the Germans, Mihailović becomes increasingly friendly with Nedić and the Nazis.

Though the Chetniks are still somewhat of a wild-card, and carry out the odd act of resistance against the occupiers, their forces are now also dedicated to the anti-communist fight against the Partisans.

All bridges are burnt by November 25, 1941 when Mihailović’s Chetniks join German and Serbian forces in their attack on the town of Uzice, the headquarters of Tito’s republic and partisan movement.

This effectively ends the cooperation between the Partisans and Chetniks, and it puts an end to Partisan resistance in Serbia, for now.

That’s far from the end of Yugoslav resistance though. Their success is not dependent on geography, but on ideology, and Tito moves his Partisans into Ustase-held Bosnia. Partisans under the leadership of Tito will continue their fight, attracting more and more fighters fleeing ethnic persecution and seeking freedom from the Nazi occupation.