Operation Haudegen – The last German soldiers to surrender after World War 2

On the 7th of May 1945, German General Alfred Jodl signed the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany at the Allied headquarters in Reims, France. It meant the Second World War had come to an end, at least, in the European theater of war. But… the war didn’t end for a small Wehrmacht unit consisting of 11 men that were housed at Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. The Wehrmacht unit was tasked with a secret mission named Operation Haudegen. They had to establish meteorological stations on Svalbard. In the chaos following the German capitulation, this Wehrmacht unit was forgotten… And these men would eventually, stuck on an island in the freezing cold, far from civilization, months after Germany’s capitulation. They would become the last German soldiers to surrender after the Second World War.

Wilhelm Dege was the commander of the mission to Svalbard. Back in 1931 he attained a teacher’s license in Germany and started his job as a teacher. After his working days, he studied geography, geology, and history. An avid explorer, he traveled to Svalbard multiple times between 1935 and 1938. The adventures resulted in his dissertation about Svalbard in 1939. He became a doctor in Geography. As Dege was teaching and exploring, Germany drifted towards an all-out war that would change the lives of every German man and woman.

In 1940 Nazi Germany, technically already at war with most of Europe, invaded Norway. Before the war broke out recruitment for the Wehrmacht consisted of 1.3 million Germans being drafted, and 2.4 million volunteering. In 1940, Wilhelm Dege was one of many that was drafted to the Wehrmacht. It wasn’t until 1943 that it was decided to launch Operation Haudegen, however. The mission consisted of geographical objectives, namely to establish meteorological stations on Svalbard. Dege knew the language, was familiar with the territory, and was an expert on what he was supposed to do. As the idea was conjured up, it became clear to the Wehrmacht command that Dege was the perfect man for the mission.

A unit of Wehrmacht soldiers was created and the men were sent to a training camp before they embarked on their mission. It was in the Goldhöhe, the German name for a mountainous area on the border between Czechoslovakia and Poland, during the Winter of 1943 a unit of German volunteers began their training.

The mission statement these men began training for was unknown, even to them. Their tasks consisted of skiing, abseiling, building igloos, controlling dog sleds, and using charts, maps and compasses in snow areas. The trainees were taught how to use measurement instruments for meteorological objectives and whatnot. Other skills such as movement in rough terrain and other survival necessities for arctic areas were drilled.

At the end of the training camp, 10 volunteer telegraphers were selected for the mission. These 10 young men had no clue as to what the mission would be. It was shrouded in utter secrecy. The brutal training regime the group was subjected to over the summer of ‘43 gave them an idea though… it certainly wasn’t going to be an easy mission.

Operation Haudegen

As the Wehrmacht unit was waiting for the submarine, Commander Wilhelm Dege briefed them on their objective. They were to establish a weather station on Svalbard and communicate weather conditions to the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine.

Svalbard was an archipelago in the Northern Icesea, over 500 kilometers north of Norway. It consisted of three large and eighty smaller scattered islands and during winter saw temperatures as low as minus 40 degrees. The islands had been discovered in 1596 by Willem Barentsz, the Dutch explorer. He gave the group of islands the name ‘Spitsbergen’. Though, in 1925, Norway changed the name to Svalbard.

By 1944 the German army was attacked from all sides. By that point, it was very evident the Axis powers were going to lose the war. Nevertheless, the Army Command wanted to be briefed on the weather forecast from the arctic area. In case of serious weather, both Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine could prepare themselves.

Analyzing, documenting, and tracking weather conditions is often a crucial element of warfare that is overshadowed by the practicalities of war. So the men were all ready and knew what was expected of them. Build up a German camp on an abandoned island far into the Arctic ocean.

In autumn 1944 a submarine, the U-307 transported the Germans to the town of Tromso, from where they sailed to Svalbard, accompanied by a weather ship, Carl J. Busch, that brought supplies so they could build up their station.

The unit of 11 Wehrmacht soldiers arrived on Svalbard around November 1944. As soon as the weather ship was unloaded and the men had their materials, both the submarine and weather ship returned to Tromso. It was the last time the Germans saw any other humans for nearly a year. The 11 men were on their own on Svalbard.

There were multiple elements that made this mission dangerous: an obvious one was the fact that the arctic winter was approaching rapidly. It could get as cold as minus 40 degrees. It didn’t take the men too long to build 2 cabins with flat roofs covered with a layer of snow and white nets. In these cabins, the men would live for the next year.

The second reason this was a dangerous mission: an Allied reconnaissance plane could fly over, or an allied warship could sail by, given that weather conditions allowed it. Once spotted, the men awaited certain capture if not death. After all, while soldiers were stuck on their arctic island they didn’t really have a strategic position… at all.

In late December 1944, the weather station was up and running. It was their daily task to send 5 encrypted weather forecasts to the weather station of Tromso, Norway. Wilhelm Dege continued his research on Svalbard in his spare time the unit was not preoccupied with sending weather forecasts.

As we already mentioned the cold on the island, especially because it was in the middle of the arctic winter the unit resided there. Thing is, a curious phenomenon called polar nights exists. Svalbard enjoyed over 2 months of them. These are the days that the sun doesn’t come up at all. For over 2 months per year, this island was, and still is, shrouded in darkness. It was tough on the unit, not enjoying any sunlight for over a third of a year. Furthermore, the risk of polar bears and other carnivores scavenging the area was present. The men could never go out of the cabin without a partner, armed with automatic rifles. Let alone the constant worries of an Allied reconnaissance plane or ship passing by and taking notice of the unit.

Life on Svalbard

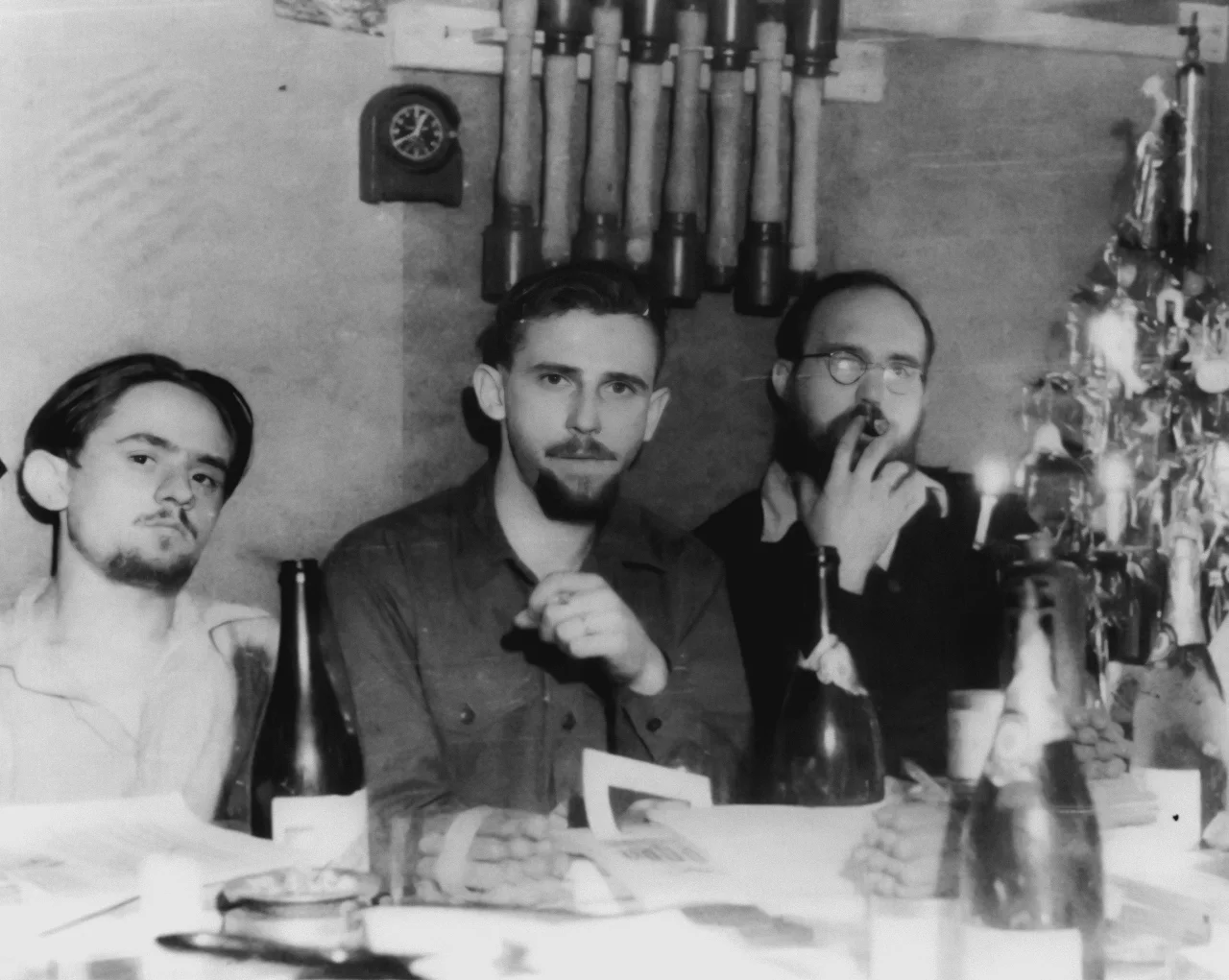

What’s so interesting about Operation Haudegen is that, regardless of the horrible conditions, the strong polar winds, lack of sunlight, and the very present risk of becoming the meal of a polar bear, the crew didn’t experience this mission as horrible. Back in 2010, Siegfried Czapka, who was 19 when he joined Wilhelm Dege and his unit, gave an interview with the German newspaper Der Spiegel. In his interview, he reminisces: “It was an incredible time. An unforgettable experience. We basically had everything, except beer”.

The unit wasn’t just physically isolated. Their radio contact wasn’t intensive either. Aside from the 5 weather forecasts a day they sent to Tromso, they weren’t engaged in war and as long as allied planes or warships didn’t spot them they wouldn’t have to be. That didn’t mean the war didn’t continue though.

On the European mainland, Germany was rapidly being pushed back over its own borders. The Germans suffered heavy losses and nearing the end of April, on the 30th, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin. It was during this time the German Luftwaffe sent the unit on Svalbard a telegram, informing about the possibility of landing a plane near the weather station to come to pick the unit up.

An improvised landing strip was swiftly constructed by the unit. They packed up and were ready to leave Svalbard, but several days went by without any news, nor any rumbling sound of airplanes, Wilhelm Dege wrote in his book “Gefangen im arktischen Eis”, recalling the Operation on Svalbard.

Instead, on their radio, they overheard the message that Germany had capitulated. Germany certainly had. On the 7th of May 1945, General Alfred Jodl signed the unconditional surrender. And as Germany and Europe were in complete disarray, there was one German unit, far north of any place men lived, that was completely forgotten…

The Forgotten Wehrmacht Unit

As we can imagine that when you’re stuck on an isolated island, in freezing cold temperatures and the radio message reaches you that your country has surrendered, with no one reaching out to you anymore…. Well… it’s a pretty unsettling experience, to put it mildly. Despair arose among the group. The men want to return to Germany, see what was left over, and help rebuild the country. Their only available option to return to Germany was to establish radio contact with the Allied powers. Germany was unavailable, so to say.

If the unit establishes contact with the Allied powers it would mean they would be arrested as prisoners of war and potentially receive lengthy prison sentences. Wilhelm Dege attempted to remain optimistic: “A unit that manned a meteorological station cannot be tried and sentenced as war criminals”.

Within a month or two the unit noticed another development. The Norwegians had returned to the weather station at Tromso. Although the unit tried to establish radio contact with them, it was near impossible to communicate. Dege passed the Norwegians their coordinates via the wavelengths used by the allied powers, but to no avail. No ships or airplanes appeared on the horizon.

As time passed Dege continued his research on Svalbard’s nature while the rest of the unit entertained themselves with ping pong inside the weather station. But then, in August, Dege’s unit received a radio message from the Norwegians. They realized the Germans were stuck on the island and would send a mission to pick them up.

In early September, a ship was going to sail to Svalbard to pick up the unit. By this point, it has been nearly 4 months since the war had officially ended in Europe. During the night of the 3rd of September, a seal-hunting ship moored near the weather station on Svalbard. While Wilhelm Dege wanted to formally surrender to the Norwegian captain Albertsen, the latter told him he had no idea how it worked. “Don’t worry, neither do I”, Dege is said to have replied.

Dege handed over his Lüger to the Norwegian captain and as such the last pocket of Wehrmacht soldiers surrendered to the Allied powers, 4 months after the official end of the Second World War.

Aftermath

As the Norwegian ship with the German unit reached Tromso, the Germans were immediately incarcerated as Prisoners of War. Nevertheless, within 3 months Wilhelm Dege was able to return to West Germany. The rest of his life was spent as a teacher and eventually from 1962 onward, as Professor in Dortmund.

Dege’s unit had been released in September 1945 already. 5 of them were from Eastern Germany, now occupied by the Soviet Union. They were not granted permission to return. They were accepted in Western Germany and eventually ended up in Eastern Germany anyway.

Over the years the 11 men met up to catch up. The youngest, Siegfried Czapka, was the last to pass away on the 12th of August 2015.

The Weather Station on Svalbard is still standing, even after all that time. It is official historical heritage of Norway and serves to remember the forgotten Wehrmacht Unit of Haudegen, over 70 years after their surrender.

After the Second World War, Wilhelm Dege wrote the book “Gefangen im Arktischen Eis”, or “Trapped in Arctic Ice”: “Wettertrupp “Haudegen” – die letzte deutsche Arktisstation des Zweiten Weltkrieges. It has been translated into English under the title “War North of 80”.

This was a nice archive. I didn’t know this story, thanks for posting it.