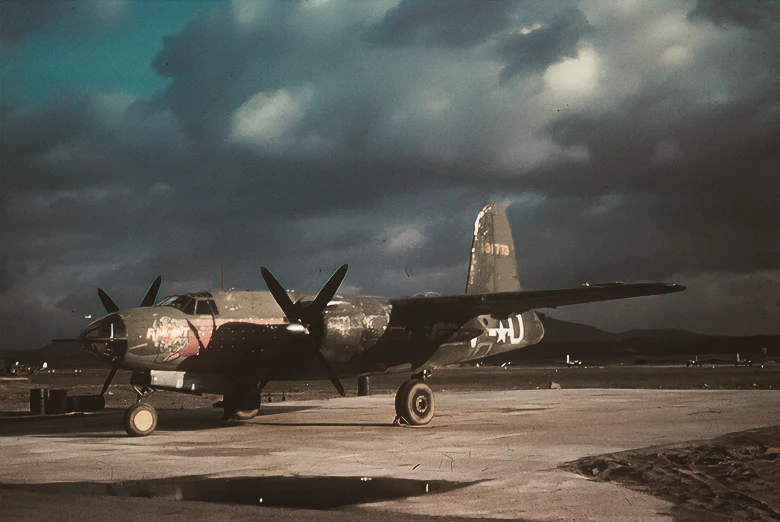

Flak-Bait – The Bomber Plane that Survived a Total of 207 Missions

"Flak-Bait" was a Martin B-26 Marauder airplane that genuinely lived up to its nickname. Throughout its career, the aircraft survived a total of 207 missions, including five where it served as a decoy to draw enemy flak fire. That's nearly twice as many total missions as most other plans flew during the war. It also notably took part in the Battle of the Bulge and D-Day at Normandy. On aggregate, Flak Bait holds the United States Air Forces record for the highest number of bombing missions conducted and survived during World War II.

The most impressive thing about the twin-engine bomber is the amount of flak it absorbed while still somehow staying in the sky. As it conducted flights across Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands the aircraft was shot over a thousand times, twice the plane managed to return to base with only one engine. Although it had almost every part of its airframe replaced at one point or another, Flak-Bait soared back to the skies from the mission after mission.

The Martin B-26 Marauder

Martin B-26 Marauders were twin-engined medium bombers used extensively in the Second World War. The aircraft was built at two factories by the Glenn L. Martin Company, one in Maryland and the other in Omaha Nebraska. It first entered service in the Pacific theater in 1942 and was later introduced to both the Mediterranean and Western European theaters.

Once an operational service, it gained a reputation amongst army aviation units as a “Widowmaker”. Rather than from its kill rate, the name came from its unreliability and a higher rate of accidents during takeoffs and landings. The primary reason for these accidents was that the Marauder needed to be flown at precise speeds, especially while on the final approach. It had a very unforgiving flight envelope. During the short final, it needed to maintain 150 miles per hour, a faster than average landing speed that was intimidating to many pilots. It was not uncommon for early models to stall and crash.

The plane was eventually safer to operate once the pilots and crews were given additional training on the model. After some aerodynamic alterations, including increasing the wingspan and adding a rudder and larger vertical stabilizer, the situation got better.

At the end of World War II, the Marauder had one of the lowest loss rates of any American bomber. 5,288 planes were produced by the end of its run in March 1945. Of these 522 were used by the British Royal Air Force and the South African Air Force. By the time the U.S Air Force was established as a standalone branch of the military separate from the army in 1947, the Marauders had been withdrawn from service.

Entry Into Service

The Marauder flew for the first time in November 1940. Only three months later, the first of these planes were on their way to the 22nd Bombardment Group in Virginia. Since the plane was sent to serve with such haste, several problems were ignored, undetected, or only emerged later on. Nose gear struts would constantly break if carrying heavy takeoff or landing loads. There were also several gear failures due to leaking hydraulics. Many of the issues could likely have been avoided if it had not been rushed to war.

Perhaps one of the most troubling aspects of the aircraft was its pairing with pilots. Most of the young pilots being sent to fly had graduated from flight schools in 1941 and 42. They were not well prepared to handle the high-speed approaches required of the airplane. Unseasoned and trained on slower aircraft, they would often land at less than 145 miles per hour, provoking the conditions that sent the plane to a roll and plunge.

The Glenn L. Martin Company addressed the handling and approach challenges towards the end of 1942. With the added modifications, they also introduced a training program initiated by General Jimmy Doolittle and carried out by Major Vincent Burnett, who helped prepare pilots for the task.

Still, in the dire months following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the crews went to battle with their bombers merely trying their best. They attempted to knock out the Japanese at Midway and failed. They attacked Rabaul from New Guinea, again with a high incidence of aircraft losses. Low-level raids against the German coast were also incredibly messy and unsuccessful. Furthermore, 10 Marauder planes were lost while attacking a power station in Holland in May of 1943 due to lethal anti-aircraft fire and deadly Luftwaffe interceptors.

Farrell’s Flak-Bait

The B-26 number 773 later known as Flak-Bait arrived in England towards the end of 1943 to become part of the 449th Bombardment Squadron. That summer, it was assigned to Lieutenant James L. Farrell and his crew of five men comprised of his co-pilot, a radio operator, his bombardier, and two gunners.

To name the aircraft, he was inspired by the family nickname for his dog “Flea Bait”. The crew believed that calling the plane “Flak-Bait” gave them an air of nonchalance about being targeted by the enemy.

Together the group flew the Marauder on its first 70 missions, the mostly part took in six-shaped formations for a total of 54 attacks conducted against airfields, marshalling facilities, bridges and roads, supply facilities, and coastal defenses. For these missions, the planes would fly in squadrons but the lead bombardier following a direction indicator on his instruments to select the target. They would all then release their bombs after the lead plane did. Most of the aircraft carried a 4,000-pound load which delivered a powerful hit when attacking as a group. Still, the Germans would not let things be that simple for the U.S.

The bomber crews faced high-velocity 88 mm Flugabwehrkanonen or anti-aircraft cannons. These would fire 15 to 20 shells per minute and each could take down a bomber if it hit close enough. The Germans defended fiercely with the explosive flak fire. They also sent up fighters to disrupt the U.S bomber’s aim while taking out as many as possible. As Flak-Bait near the target areas, it often entered storms of these shots and more than lived up to its name. To avoid the anti-aircraft fire, the pilots relied on invasive maneuvers but in the last seconds before and during a bombing run, there was little the Marauder could do.

In a 1978 interview with Air Power Magazine, Farrell stated “We figured it took the flak gunner 17 seconds to target us and another 13 before the shell started bursting. For that reason we wouldn’t go 30 seconds without doing something, climbing and turning to the left, descending and turning to the right, etc.”

Yet during the final 30 seconds of a bombing raid, the pilots had no choice but to fly straight, leaving them incredibly vulnerable to enemy fire. On almost every mission, Flak-Bait came back having absorbed at least one hit and usually with far more. Flak-Bait reportedly had every single control surface replaced at least once with the hydraulics and electrical systems also getting wholly swapped out.

Twice it flew back to its base on only one engine. On one occasion, it flew with the dead engine while the other was on fire. While most of the hits were scored by German anti-aircraft guns, the Luftwaffe fighters also inflicted several blows.

Farrell also recalled the following during the same interview in 1978: “We had so many encounters with them early in the war and my feelings we became too tough for them. We were knocking down more of them than they were of us.”

Increasingly though, the U.S was sending more planes while the Luftwaffe became weaker. Many of their fighters had to be withdrawn to protect the heavy bombing raids against German land and were less and less used in the occupied territories with the B-26s operated. Still, the Flak-Bait crew did fight back as much as possible whenever they encountered an enemy fighter.

Towards the beginning of September 1943, Flak-Bait was sent on an attack against rail marshalling yards in France, and the formation was met by a swarm of Messerschmitt Bf 109s. One shot from an enemy 20 mm cannon entered Flak-Bait through the nose. It made a clean path to the instrument panel where it exploded, injuring both Farrell and his bombardier Owen J. Redmond. They returned to base at Braintree England with only the airspeed indicator working.

After recovering from the attack, Farrell and his crew boarded the plane once more for the attack on Normandy, which Farrell later recalled stating: “D-Day was a rainy rotten day and we went out about 4:30 in the morning. We got up to high altitude and even though it was June there was a lot of ice. There was a miserable cold wave that came through there, we had the whole group and I was a squadron leader.”

The B-26s were first tasked with taking on 155 mm gun bunkers that threatened the beach landings and several light anti-aircraft positions that threatened the amphibious landings’ air support. Later missions in the day would soften up German ground forces for the Allies to break out of their beachheads. In total, Flak-Bait flew three different missions with three different crews in less than 24 hours.

Farrell’s crew was sent home in July of 1944. The plane continued to serve in others’ hands for the rest of the war including making an appearance during the Battle of the Bulge. During the surprise German offensive, Flak-Bait targeted both the German advance and subsequent retreat by taking out roads and bridges.

By April 1945, the aircraft completed its 200th mission which surpassed all other U.S bombers at the time. During that operation, it struck the German homeland with a raid on the city of Magdeburg. At the end of the war, Flak-Bait had been used in 207 missions. It was only stopped by the retirement of the aircraft type, in favor of the perhaps confusingly named Douglas A-26 which would later also take on the name B-26.

B-26 to A-26

Once the Douglas A-26 Invader took over the original B-26’s role, depot workers at two locations in Germany destroyed all remaining Marauder aircraft for scrap aluminum. In this way, they could save money on flying them home. The Flak-Bait however, was safe from this fate due to its incredible history. It was selected to feature in a display at the National Aeronautical Collection maintained by the U.S Army Air Forces. The exhibit focused on the aircraft that played a key role in winning the war.

Flak-Bait was flown one last time on March 18th 1946 by Major John Egan and Captain Norman Slusher to an air depot in Bavaria. It was disassembled at the site, placed in crates, and shipped to a Douglas factory in Illinois in December 1946. Flak-Bait has since been under conservation at the Smithsonian Institution in its National Air and Space Museum. The remarkably resilient aircraft now has painted red bombs on its side, each one representing a mission. A lone black bomb represents its one night mission while five ducks represent its decoy missions.