Stopping the Nazi Atomic Bomb

Just why was Germany so interested in the remote Vemork hydroelectric facility? Nestled in the southern mountains of Norway, and perched on a ledge overlooking a deep valley, the site harbored a dark secret. In the 1930s and 40s, it was the only plant commercially manufacturing heavy water, a key component in the production of nuclear weapons. When Norway was invaded by Germany in 1940, concerns mounted that the Germans would seize the plant and its heavy water facilities and control most of the global supply. Tensions were high, as German scientists had already discovered nuclear fission two years earlier. Due to the extreme secrecy, no one knew how close the German weapons program was to successfully producing an atomic bomb, but the Allied Powers were not about to wait around to find out.

The Plan

Due to its relative inaccessibility, means of infiltrating the plant were limited and dangerous. The bridge across the valley below the plant was heavily guarded and the mountains above had been rigged with landmines. Bombing the plant was out of the question, both due to risk of civilian casualties and more vitally, the supply of heavy water was buried in the plant’s basements deep underground.

Likelihood of overhead airstrikes destroying the supply was low. It would take a creatively designed stealth raid, led and carried out by Norwegian commandos in the dead of winter to do substantial damage to the heavy water supply. If the mission failed, there was the chance that Germany could get the bomb first and swing the war in their favor.

Heavy water

The heavy water facility at Vemork had been added to the plant after its opening in 1911. It was Norwegian physicist and professor Leif Tronstad who first put forward the proposal of producing heavy water to Norsk Hydro in 1933, the same year that heavy water was first chemically isolated.

The term “heavy water”, refers to a specific enriched water mixture that combines D20 or deuterium oxide with hydrogen-deuterium oxide and ordinary H20. It by all appearances looks feels and tastes like regular water. But the presence of deuterium atoms, cause it to be 11% denser than H20, allowing it to act as an effective neutron modulator in nuclear reactions. Slower-moving neutrons like those passing through heavy water are more effective at splitting atoms.

Tronstad was incredibly interested in the scientific possibilities of heavy water but at the time was unaware of the connection between heavy water and atomic weaponry. Not realizing the dangerous path they were heading down, Norsk Hydro accepted and production began in 1935.

Captain Tronstad

As the war raged on in Europe in 1940, Tronstad chose to focus his efforts on resistance activities. He had previous military experience prior to becoming a scientist and after the Nazi invasion of Norway, he set up a communication channel that passed information on Nazi activity across borders and on to the British. Once the Nazis caught on to this in 1941, he was forced to flee his country.

Tronstad went to England where he became chief of intelligence for the Norwegian government in exile. Tronstad still had informants at the plant, however, including his old co-worker Jomar Brun who was still in charge of operations. Tronstad used this connection to continue relaying information about the goings-on there under Nazi control. By the end of 1941, reports word of the plant ramped up its operations by a hundred kilograms per month, producing four kilograms of heavy water a day.

Concerned by this development amid whispers of a secret Nazi atomic project, Tronstad and the Combined Operations Headquarters in England decided to take action.

Operations Grouse and Freshman

It was Tronstad himself who pitched the idea of a stealth commando raid on the plant. He was too important to the war efforts in England to risk losing him by participating in the raid himself but he was integral in hand-selecting a team of 9 Special Operations Executive trained Norwegian commandos and he also assisted in their training. The men chosen underwent months of survivalist training in Scotland to prepare for winter conditions in the mountains of Norway.

As a preliminary measure, a reconnaissance team would go in first to survey the plant and its surroundings and set up a means of communication. On October 19th, 1942, 4 commandos were parachuted into Norway, landing on a peak above the plant called the Hardanger Plateau. The directive was to gather as much intel as possible via surveillance and plant radio beacons for future teams. This was known as Operation Grouse.

The commandos had to approach the plant on skis from their drop point eventually reaching the forests nearby after losing their course several times due to bad weather and unfamiliar territory. They took so much extra time that when they finally did report back to headquarters in England, the superiors were suspicious and asked them the coded question they had arranged. “What did you see in the early morning?” to which the commando replied “Three pink elephants.”

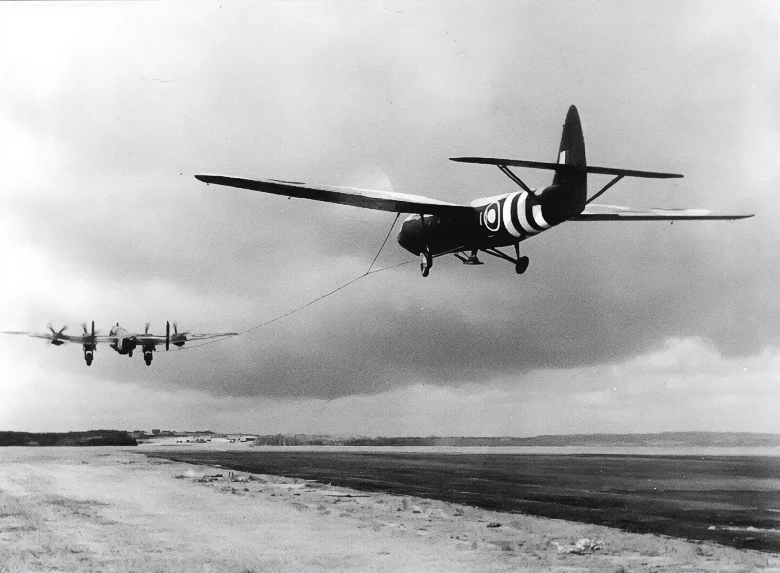

Following the report in, the next phase of the assault and the plant commenced. Nicknamed Operation Freshman, the plan would be to land two gliders each carrying 15 Royal Engineers in the British Army on a frozen lake near the plant. They set out on November 19th, exactly a month after Operation Grouse.

The two gliders were each towed by a Royal Air Force bomber. The weather conditions upon entering the mountainous area was especially treacherous and visibility extremely low. The first bomber crashed into a mountainside, killing 7 men onboard. Its glider was able to cast off but it also crashed nearby and the Royal Engineers perished. The second glider managed to make it to the area at the plant but its pilots were unable to locate the exact drop point below.

After circling the area for some time and with fuel running low, the pilots decided to turn back. However, on their return, they passed through a heavy cloud and the resulting turbulence caused the cable connecting glider to the bomber to snap. The glider fell from the sky and crashed below. The few survivors of the crash were discovered by Nazi troops, rounded up, and delivered to the Gestapo.

The calamitous operation was made all the more so because now the Allied forces had not only lost men and time but the Nazis were made aware of their efforts to destroy the heavy water supply at the Vemork plant. Additional, guards, landmines, and floodlights were added to the security surrounding the plant, if they were to try again the Allies would have to be extremely cautious.

Operation Gunnerside

After the failure of Operation Freshman, the members of the Operation Grouse party were left alone in the mountains for months, camping out and waiting for instructions in a harsh Norwegian winter. They had not planned to be out so long and had run out of food supplies. They became so hungry they began to eat moss and lichen until finally, they were able to track and kill a reindeer.

The forces back in England were aware that the Grouse team had survived and made plans to drop the remaining 6 trained commandos nearby. The goal was to locate the Grouse team and to get her sneaked into the plant and destroy the heavy water supply within.

The operation, coined Operation Gunnerside, commenced on February 16 1943 when the commandos were successfully dropped into the area from a Halifax bomber under cover of night. Using cross-country skis, the team quickly surveyed the area and rendezvous with the Grouse team. Together, they spent several nights strategizing on the best way to approach the plant.

The mountain above the trap was heavily rigged with landmines, an extra guard had been added to the bridge across the ravine. They decided the safest way to approach the plant would be to hike down into the ravine, cross the river within, then scaled a steep wall directly below the plant.

The team set off on the night of February 27th, they crossed the river successfully, climbed their way up and out of the ravine, and followed a set of railroad tracks to the plant itself. They arrived at the plant at 12:30 a.m. Using wire cutters, they were able to cut quickly and quietly through the security fence surrounding the plant, they were in.

Because of Captain Tronstad’s inside information on the plant’s guard rotations and security schedule, they were able to infiltrate it without encountering a single Nazi guard. The commandos split into two teams, a 4 men explosives team and 5 men lookout team. Using maps of the plant provided by Tronstad, a demolition group had planned to enter the heavy water area through a side door, which they located, but found to be locked. Instead, they found an access tunnel that could crawl through on hands and knees and successfully rappel into the heavy water facilities. Only two of the five men emerged from the tunnel at first, the others getting lost or separated on route. Then countered a night shift worker and a foreman in this area of the plant, they were both Norwegians themselves and sympathetic to the cause. They readily stepped out of the way and the commandos assured them that no harm would come to them.

With time of the essence, the two commandos decided not to wait for the others and they began to prepare the explosives which involved laying two strings of charges around the 9 electrolysis chambers. As they were rigging up the ninth chamber, a window crashed in behind them and they spun around, prepared for a fight, but it was just the 3 remaining members of their team finally locating the facilities themselves.

They finished setting up the explosives, cutting the fuses down from a two-minute length to a thirty-second length to ensure they ignited successfully. The two plant workers were told to run upstairs and lie down, holding their mouths open so their eardrums wouldn’t be damaged. They lift the fuses and scattered, the explosives detonated successfully, though the commandos reported later that it wasn’t nearly as loud or explosive as they were expecting.

500 kilograms of heavy water, the entire supply that had been produced under Nazi supervision since 1940 was destroyed, along with all of the equipment used to produce it. The team purposely left a British model machine gun behind to indicate British involvement and to discourage the Nazis from retaliating against the local resistance.

The commandos escaped into the night on their skis, splitting up to minimize the risk of being captured. Four of them skied 400 kilometers east to Sweden, two went to Oslo, and the rest stayed behind to continue to assist in resistance activities.

The Germans did eventually catch on and sent 3,000 Nazi troops after them, with search aircrafts hovering overhead but they were too late. All of the commandos had escaped successfully.

The Nazi Atomic Bomb

Back in Britain, Tronstad received confirmation that Operation Gunnerside had been a complete success. The heavy water facilities had been destroyed with zero casualties or complications. Tronstad was thrilled, but because the commandos themselves were not fully aware of the atomic possibilities of heavy water, they did not comprehend the full scope of what they had accomplished until 1945 when the U.S. manufactured nuclear weapons were dropped on Japan.

British Special Operations called Gunnerside the most successful sabotage mission of World War II. The Vemork plant did eventually get back up and running the following April, an additional attempts were made to bomb the facilities by both the US Air Force and the RAF but they made a little impact.

Rumoured eyewitness accounts documented by the KGB, alleged the Nazis did indeed complete an experimental nuclear weapons test in either late 1944 or early 1945. It seems Gunnerside had done the heavy lifting and delaying the Germans just enough, and perhaps played a pivotal role in the delay of their atomic weapons program.

Records related to the witness accounts were reportedly suppressed or destroyed, leaving us to wonder just how close the Nazis really were to an atomic bomb, for now, we remain in the dark.