Operation Vengeance – Killing Admiral Yamamoto

Enraged over the sneak-attack on Pearl Harbor, just going to war with Japan over was not going to be enough to calm the fury of the United States. The American Government believed that the clearest course of action would be to get direct revenge on the man who planned the strike. With help from Japanese-Americans, the U.S. intelligence community launched Operation Vengeance and began to track the movement of Japanese Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto across the Pacific Theater. When the Magic code breaking unit intercepted his itinerary in April of 1943, FDR himself allegedly gave the simple order, “Get Yamamoto.” A squadron of P-38 Lightnings was quickly sent aloft to take down the Admiral…

Isoroku Yamamoto

Isoroku Yamamoto was one of the most notable leaders of the Japanese Empire, and he is credited with planning and executing the attack on Pearl Harbor, a preemptive strike against a neutral country that was judged a war crime at the Tokyo Trials once the war was over.

Yamamoto held several posts in the Imperial Japanese Navy throughout his career and was a major architect of the country’s naval aviation program. He served as commander in chief at the beginning of the Pacific War and was in charge of several key battles during World War II.

Interestingly, Yamamoto was not only highly educated, intelligent, and successful in his activities but he also had a deep understanding of the United States. He had studied at Harvard and was familiar with everyday American life and the country’s military prowess. Perhaps that awareness of American capabilities was part of why he opposed engaging in a military conflict with the United States and the allies at large.

He’s known to have stated: “In the first six to twelve months of a war with the United States and Great Britain, I will run wild and win the victory upon victory. But then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectation of success.”

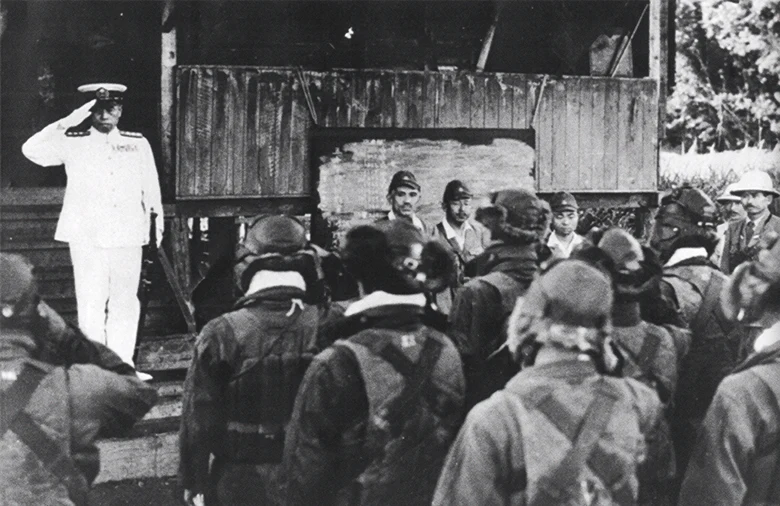

While he personally felt that Japan had taken the losing side in the long run, Yamamoto was loyal to the Japanese cause and served his country as best he could. For this, and his overall performance serving Japan, he was highly celebrated and beloved by the Japanese.

In understandably stark contrast, in 1943, he was one of the most hated people in the United States, with civilians and politicians thinking of him as a treacherous character who had stabbed America in the back while it attempted to remain neutral and peaceful.

While the characterization of the Japanese leader was not completely incorrect as he committed a war crime for his country, it wasn’t totally accurate. Since the United States was expected to support the Western European effort at some point based on its ongoing passive interference. That same year, the United States captured Guadalcanal, putting the Japanese in deep trouble and prompting Yamamoto to visit naval air units to assess the damage.

Operation Vengeance

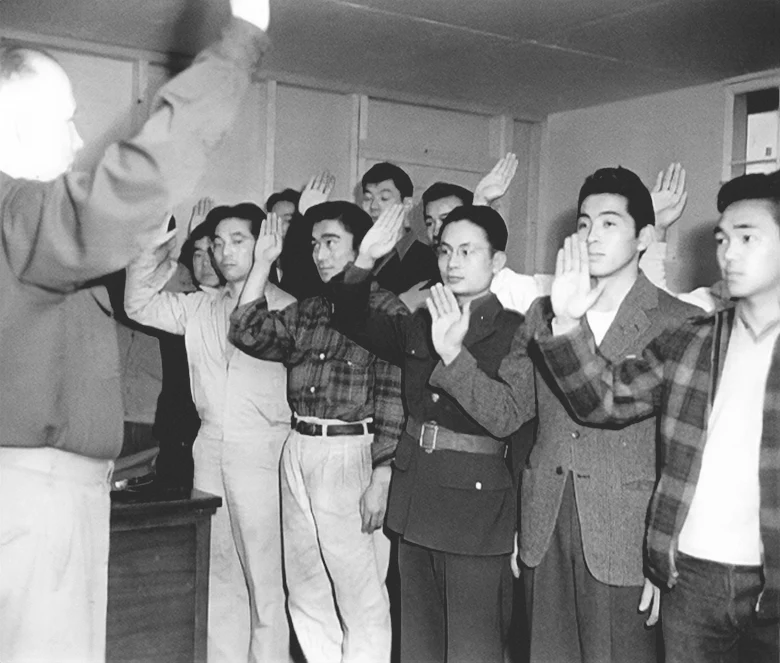

The Japanese acted as they normally did and sent a coded message on April 13th of 1943 to the commands in Guadalcanal to let them know the Admiral’s itinerary as well as details about transport and exports. Unknown to them, the Military Intelligence Service had been able to intercept their communications for years. MIS soldier Harold Fudenna has been credited with intercepting the radio message.

The message was sent using a brand new JN-25D code, but Nisei-second generation Japanese Americans assisted in decoding the message. Those Nisei employed by the MIS were often involved in extracting information from documents and captured individuals in the effort against Japan. Additionally, linguists in Alaska and Hawaii also interpreted intercepted messages that confirmed the accuracy of the information.

The MIS was able to surmise that Yamamoto would be traveling in a straight route from Rabaul to the Balalae Airfield, a distance of 315 miles, which allowed them to theorize more or less where he would be during each minute of the flight. In order for the attack to go as planned, they would need the Japanese pilots to act reliably with no delays or changes to the itinerary.

The U.S Commander in the Pacific, Admiral Chester Nimitz approved an operation put forth by 339th Squadron Commander Major John W. Mitchell, who estimated that the Japanese naval leader could be intercepted before landing at Balalae at exactly 9:35 a.m.

One main consideration for Operation Vengeance was which type of aircraft to use for the attack. Certain fighter aircraft like the F4F Wildcat did not have the range needed to reach the aircraft flying over Bougainville, which was 400 miles away from the American air base in Guadalcanal.

The only American aircraft considered to have the necessary range and qualities to be used for the mission was the Air Forces’ Lockheed P-38G Lightning. Yet, the plane had aspects that complicated the operation. To avoid detection, the pilots would need to fly at least 50 miles away from the shore, dead-reckoning at an altitude of 50 feet or less.

Furthermore, the Lightnings lacked an AWACS radar aircraft or land-based radar to get the pilots to the target. Not much external guidance support could be added without risking attack by the Japanese forces stationed in the area. To navigate with the required precision, the Lightnings were equipped with navy compasses at the request of Mitchell himself.

Execution

339th Squadron Commander Major John W. Mitchell led the charge on April 18th, 1943. 18 P-38 Lightnings chosen to target the Admiral were each equipped with their standard 20 millimeter cannon and four machine guns. They carried additional drop tanks so they could make the long flight.

18 planes were chosen for the mission, and four of those were selected to attack Yamamoto’s aircraft while the rest climbed above to form a cover against the Japanese escorting fighters. The pilots involved were briefed with incomplete information, being told that they were attacking a high-ranking Japanese officer who had been spotted by a coastwatcher. They did not know who the specific target was or the extent to which MIS was involved in locating him. This account of events has been partially contradicted by a witness who claimed Mitchell revealed that Yamamoto was the target in order to motivate the pilots.

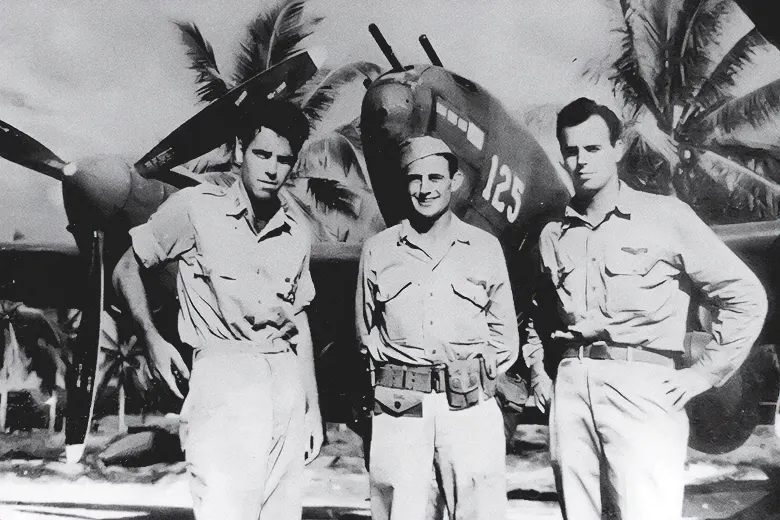

At 7:00 a.m. that morning, only 16 of the intended 18 planes took off from the field because two of the pilots assigned to the kill squad saw their planes compromised, one to a flat tire and the other to a faulty fuel feed. The two pilots who made the flight out of the four selected to carry out the kill were Captain Thomas G. Lanphier, and Lieutenant Rex T. Barber.

They traveled 400 miles at low altitude in complete silence, and with an estimated low probability of success. It was the fighter intercept mission requiring the longest distance flight of the entire war.

Calculating the wind speed, flight path, and speed of the Japanese G4M “Betty” carrying the Admiral, the Americans expected to intercept at exactly 9:35 a.m. The U.S. team arrived one minute earlier than needed, at 9:34, and their intel was proven correct when the Japanese aircraft appeared in the next minute.

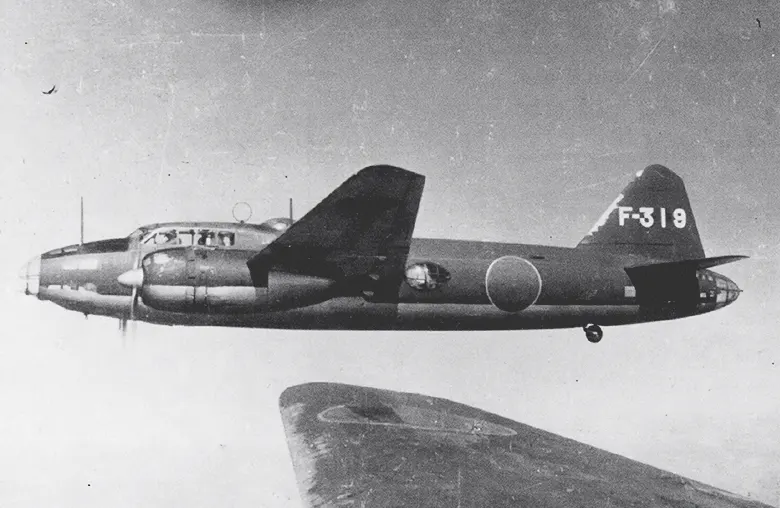

Two Betty bombers, one of which carried Yamamoto, entered into the view of the Lightning planes at 4,500 feet. They were escorted by six A6M “Zero” fighter planes at 5,500 feet. 12 of the American planes flew up to 18,000 feet, undetected, while the other four attacked the Japanese bombers.

The bombers dove to evade the attack, while Captain Lanphier and Lieutenant Barber pursued them without knowing which of the two carried their target. Reportedly, Lieutenant Barber shot at one of the Bettys and did successfully damage its right engine, sending it straight into the jungle. The other one was allegedly shot by Lieutenant Holmes, which forced it to crash-land into the sea. In the jungle, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s body rested with his sword in hand.

Aftermath

Yamamoto was retrieved the following morning. It was ruled that he had passed before the crash. His cremated remains were sent back to Tokyo on the IJN Musashi. Mineichi Koga stepped in as commander in chief and was soon changed for Soemu Toyoda. Neither was able to command as effectively as Yamamoto had done.

On a strategic level, the United States had acted effectively. The trip to Guadalcanal, which the Japanese Administration had hoped would boost morale, was a devastating blow. The fall of Yamamoto was kept as a secret from the Japanese public for a month.

In Japan, the aerial battle would be called the “Navy kō incident”. Admiral Ugaki, who survived the ocean crash of the other Betty accompanying Yamamoto’s plane, recovered to direct some of the largest kamikaze attacks against the U.S. in the end stages of the Pacific War.

When Japan surrendered in 1945, he reportedly boarded a Yokosuka D4Y with the intention of never returning. Two of his subordinates got on the plane with him in an attempt to dissuade him. None of them were ever seen again, and no U.S. records had been linked to his disappearance.

For the United States, the successful mission represented a point of great pride in the greater conflict. The hide that they had read the Japanese codes, all American newspapers and broadcasters were told the fake story used to brief the squadron, that coastwatchers had seen Yamamoto entering his bomber in the Solomon Islands.

This way, the American military could claim that the kill was a matter of luck, rather than the product of intelligence efforts. Japanese were more than happy to accept this version of events and failed to realize many of their ciphers had been broken.

Controversy

Despite the success in the mission, controversy followed the incident for years. The pilots involved were not debriefed after the mission. As there were no interrogation procedures established in the area back then, only Lieutenant Holmes was able to give his account, stating that one Betty was taken down by him, and the intelligence community assumed that was all there was to it.

Captain Lanphier and Lieutenant Barber both took credit for downing Yamamoto’s plane and each was given half credit.

Six months after the operation, some of its details were leaked to the press, with Time Magazine reporting Captain Lanphier’s involvement. This represented a breach of Navy security, since identifying him by name made him a target for retaliation.

As a reprisal, Major John Mitchell was given the Navy Cross rather than the more prized Medal of Honor. All other pilots in the killer portion of the squad were given the same honor.

Lieutenant Barber formally petitioned to have his half credit changed to a full credit, but in 1991, the Air Force History Office ruled that sufficient uncertainty remained in the case for both Captain Lanphier’s and Lieutenant Barber’s claims to be accepted.

A close friend of both officers would later claim that Captain Lanphier had composed the official report, the medal citations, and several articles about the mission published in magazines.

Additionally, it has been claimed that while Lieutenant Barber had been willing to share half of the credit at first, Lanphier had written a manuscript for a memoir claiming full credit. Even though the book was never published by Captain Lanphier, he continued to take credit throughout his life, which Lieutenant Barber continued to strongly contest.